Football is not the same anymore. Gone are the days of defenders, midfielders and strikers. It has become way more complicated.

Nowadays you have No 6s, No 8s, false nines and inverted full-backs. Route-one balls are now known as verticality while counter-attacks have become transitions.

What it has led to is a completely different language when it comes to football. Take this quote from Erik ten Hag in September 2023:

What on earth does that all mean?

Well, we’ve taken the time to come up with a new, alternative football dictionary to help you understand what managers are saying nowadays…

Expected Goals (xG)

Expected goals (xG) measures the quality of a chance by calculating the likelihood it will be scored from a particular position on the pitch during a particular phase of play.

xG is measured on a scale between zero and one, where zero represents a chance that is impossible to score and one represents a chance a player would be expected to score every single time.

This value is based on several factors from before the shot was taken, including the distance to goal, the angle of the shot or the body part of the attacking player used for the shot.

The xG of each shot in a game is added up to reach the overall tally for each game, to show how many goals a team should have scored.

There is also Expected Goals on Target – which only record the quality of shots heading towards the goal, rather than off target – and Post-shot xG, which measures the chance’s quality after the player has connected with the shot.

Transition

You hear this a lot when managers speak. “We were really good in the transitions today.” But what do they mean?

Well, a transition is when one team loses the ball and the other team gains possession. That’s the simple bit.

But the reason why they are so important is because the team that loses the ball is disorganised, allowing a few split seconds for their opponents to catch them out and put them into an even more challenging position.

So if your team is sharper when the opposition lose the ball, you have a better chance of scoring.

Overload

Pep Guardiola’s dream. Simply put, overloads are all about gaining a numerical advantage over your opponent in a specific area of the pitch.

An overload in possession would refer to having more attackers than defenders in a certain part of the pitch, while out of possession is having more defenders than attackers in an area.

The most simple and common overload in possession would be when a winger is joined by their attacking full-back when attacking an opposition full-back. The full-back could make an overlapping or an underlapping run to create space or be an additional option to isolate the opposition defender.

But there are other forms of overloads too. For example, Cole Palmer drifting from the attacking midfield role to the right wing creates an overload on that flank with Noni Madueke.

Rest defence

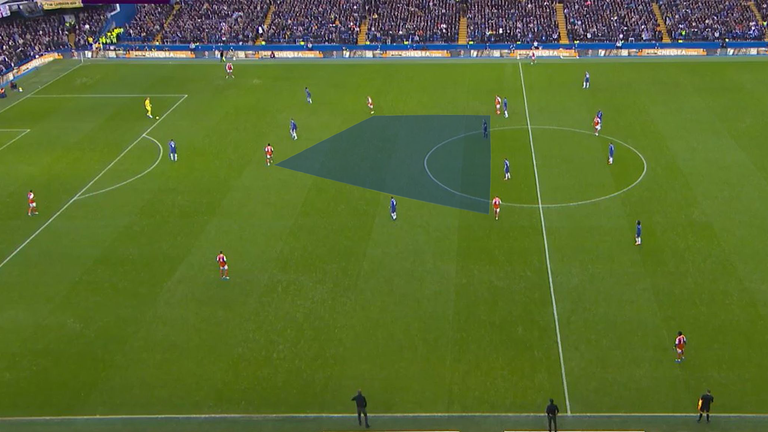

One thing that can help a team defend against transitions is having a good ‘rest defence’. These are the positions a team’s defenders take up while their team is attacking, to stop them being counter-attacked.

For example, Arsenal use their inverted full-back to create a block of five players to protect the middle of the pitch. If they lose the ball and end up in transition, their players can simply run back in a straight line to snuff out a potential counter.

Brighton manager Fabian Hurzeler explained what makes an effective ‘rest defence’ to Sky Sports earlier this season: “How good is your positioning with the ball? How close are your pass distances to each other when you lose the ball? Do you have a close net to each other so you can avoid counter-pressing and transition moments from the opponents? It’s about positioning and the distance between each other – but it’s also about scanning the field.”

Inverted full-back

A full-back playing as a midfielder. It’s becoming more and more common in the game.

Most teams do it to create a ‘box midfield’ of four players in order to get an overload in the middle of the pitch, the most important area.

If you have that box of four, it doesn’t matter if you play against two or three central midfielders, you will always have a spare player in the middle, allowing you to control games a lot more.

Verticality

You know that side-to-side-to-side-to-side patient passing that can sometimes come across as tedious? Well, the opposite of that is verticality.

That is a more direct style of passing the ball. Verticality is when teams play through and try to break the lines instead of trying to go around teams.

Andoni Iraola’s Bournemouth, for example, are known for their vertical passing.

False nine

If a traditional striker is a true No 9, then what is a false nine?

That is when a striker drops deeper into midfield positions to get on the ball earlier and/or bring other attacking players into the game.

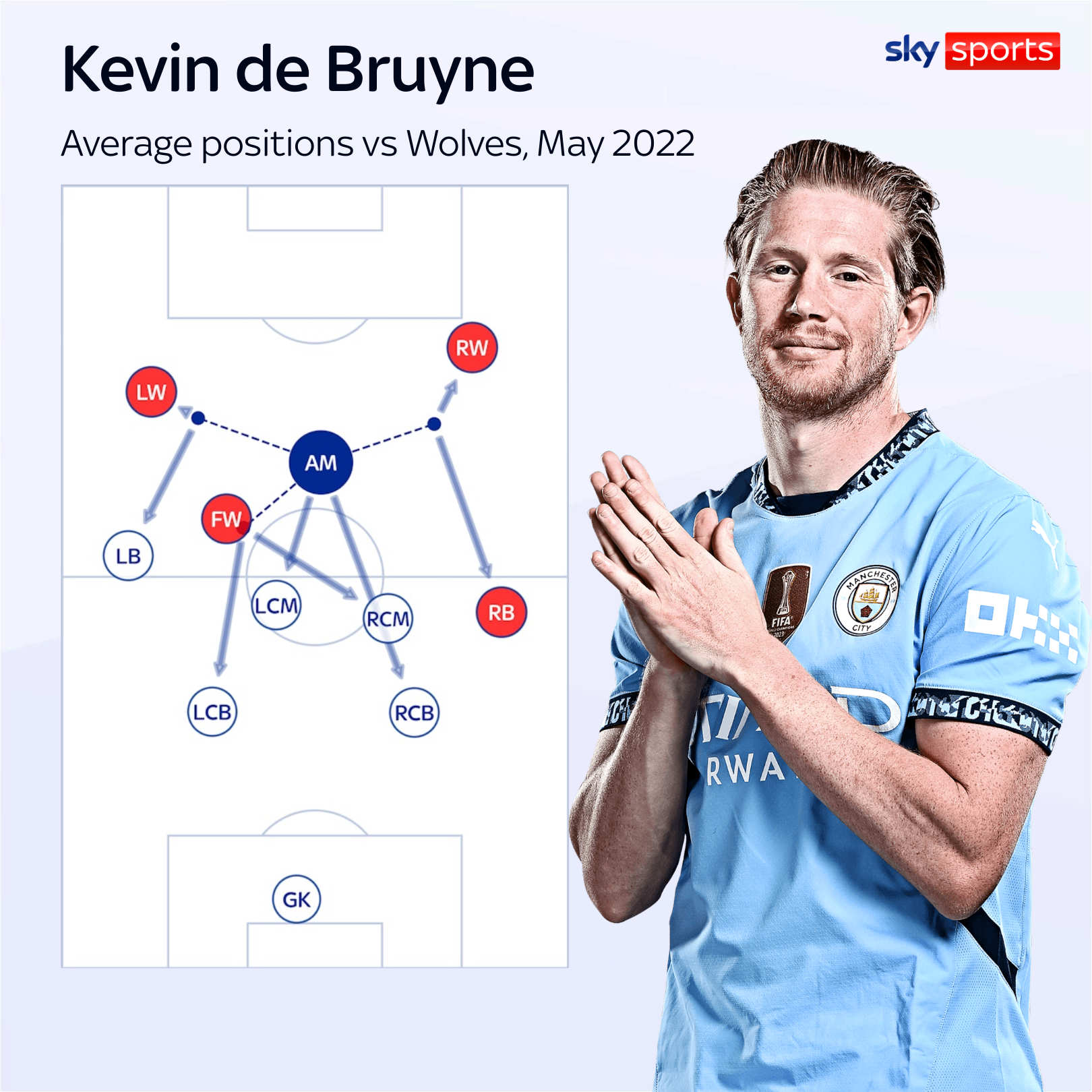

Sometimes, managers would even play a midfielder in their striker role to achieve this. For example, Pep Guardiola often used Cesc Fabregas as a false nine while at Barcelona, while he has replicated that with Kevin De Bruyne and Phil Foden in recent years at Manchester City.

And what’s a false 10?

Well, that’s the opposite of a false nine.

Instead of a striker moving backwards into midfield, it’s a midfielder moving forwards into a striker role.

This moves the midfielder in the blind spot of the defensive midfielders into ‘goalside’ areas, meaning if they get the ball and turn, they are able to charge at the opposition defence.

At Brighton, Joao Pedro and Georginio Rutter are adjudged to play in ‘false 10’ roles as on paper, they are midfielders. But they also join Danny Welbeck in the forward line quite a lot. Brighton manager Hurzeler discusses more in the video below…

Libero

Right, so to make this more confusing, there are two definitions of a ‘libero’ – the old version and the modern one.

Coming from the Italian word ‘free’, a libero in football is a central defender who moves into different areas of the pitch from his other central defender(s). Back in the day, a libero would be a sweeper defender who sits deeper than his team’s backline to mop up attacks over the top.

But since the evolution of a ‘sweeper keeper’ where a goalkeeper would do that role instead, a libero now means a defender who steps out of the backline and plays a more attacking role.

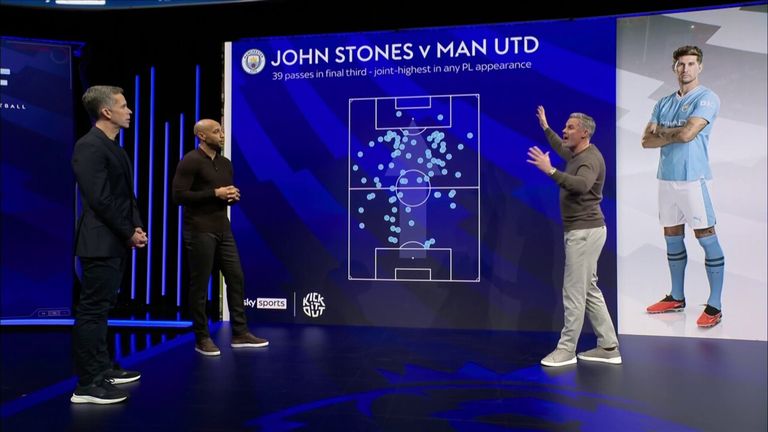

See (and you’ve probably worked this out by now) John Stones as a good example. One minute he’s a centre-back, the next minute he’s a No 10.

Regista

Regista is just a fancy word for a deep-lying playmaker, like a quarterback in American football. On paper, these players are sitting midfielders but they control the tempo of the game and create chances from deep, largely from passing the ball.

We know, you’re basically thinking of Rodri. But he’s a regista-like player. Because this term is normally given to technically brilliant defensive midfielders who do not excel physically. Because Rodri has both, he doesn’t really count.

The best example of a regista is Andrea Pirlo, who was successful in creating chances from deep, but was also reliant on having a defensive midfielder like Gennaro Gattuso beside him.

Perhaps a better modern example is Angel Gomes of Lille and the England national team.

High line

If you’ve watched Ange Postecoglou’s Tottenham, Unai Emery’s Aston Villa or Hurzeler’s Brighton, you’ll be more than familiar with the concept of a high line.

Put simply, when a team is in possession, a high line refers to the defenders staying close to the middle of the pitch. Deploying the tactic ensures reduced space for the opposition and greater numbers up the field which allows attacks to be recycled, pinning the opposition in their own half.

It also allows you to catch your opponents offside, meaning you can regain the ball a significant distance away from your goal.

High press

So the opposite of a low block is a high press, where teams will look to win the ball up as high up the pitch as possible. It can be an effective weapon as if you win the ball, you could be between one or two passes from scoring.

But high pressing is not an individual skill, it is a collective one. It is not just one player pressing, it is the entire unit trying to force a mistake from the opposition. Players will hunt for the ball in groups of three or four or even more.

High pressing does not involve everyone going directly for the ball. One player might do that, while other players block off passing lanes – i.e standing in front of a passing target for the player in possession to give them fewer options.

Low block

When teams sit in a low block, that is when they sit very deep and compact on the pitch, while forcing the opposition to break them down.

A team playing a low block denies the opposition space in the middle of the pitch and puts more and more defenders behind the ball until they are in their own penalty area, where you would expect every single player to be behind the ball, defending.

Teams who have a low block will then look to counter-attack against their opponents once they have the ball and the opposition have committed enough players forward to inflict an effective fast break.

But teams who play a low block are not limited to just sides who are playing against superior opposition. For example, Mikel Arteta’s Arsenal will look to press teams high in a certain area of the pitch but will then move into a low 4-4-2 block if that press is beaten.

Mid-block

So if you have high pressing and a low block, then what on earth is a mid-block? Well, it’s something in between the two.

A team doing a mid-block is not pressing too high up the pitch, nor sitting too deep. The aim is to stop the ball moving too much in the middle of the pitch. That could be because an opposition’s most dangerous player is a central or attacking midfielder.

But a mid-block can also tempt the opposition to play out of the back, which can then be met with a high press.

Counter press

This has also been known as ‘Gegenpressing’ or the ‘Barcelona press’ when Pep Guardiola was in charge of the Spanish club.

Counter-pressing is the quick, intense desire to get possession back as soon as you lose the ball, with the aim to retrieve it within a matter of seconds. It is different from normal pressing, which can take a longer amount of time.

“Gegenpressing lets you win back the ball nearer to the goal,” said Jurgen Klopp. “It’s only one pass away from a really good opportunity.

“No playmaker in the world can be as good as a good gegenpressing situation, and that’s why it’s so important.”

Pressing triggers

When Demba Ba capitalised on a lax touch by Steven Gerrard to score one of the most famous goals in Premier League history, there was far more at play than just a bit of luck and a slip.

What the then-Chelsea forward was doing is capitalising on a pressing trigger. In this case, a heavy touch was the trigger that meant the Ba could react, press high and win the ball.

Pressing triggers refer to situations on the pitch that give a player the chance to win possession of the ball.

In these scenarios, players are trained to recognise cues such as a poor touch or pass, a player receiving the ball with a certain body shape or a slow reaction when receiving the ball. These all might cause players to set off their press and try to win the ball.

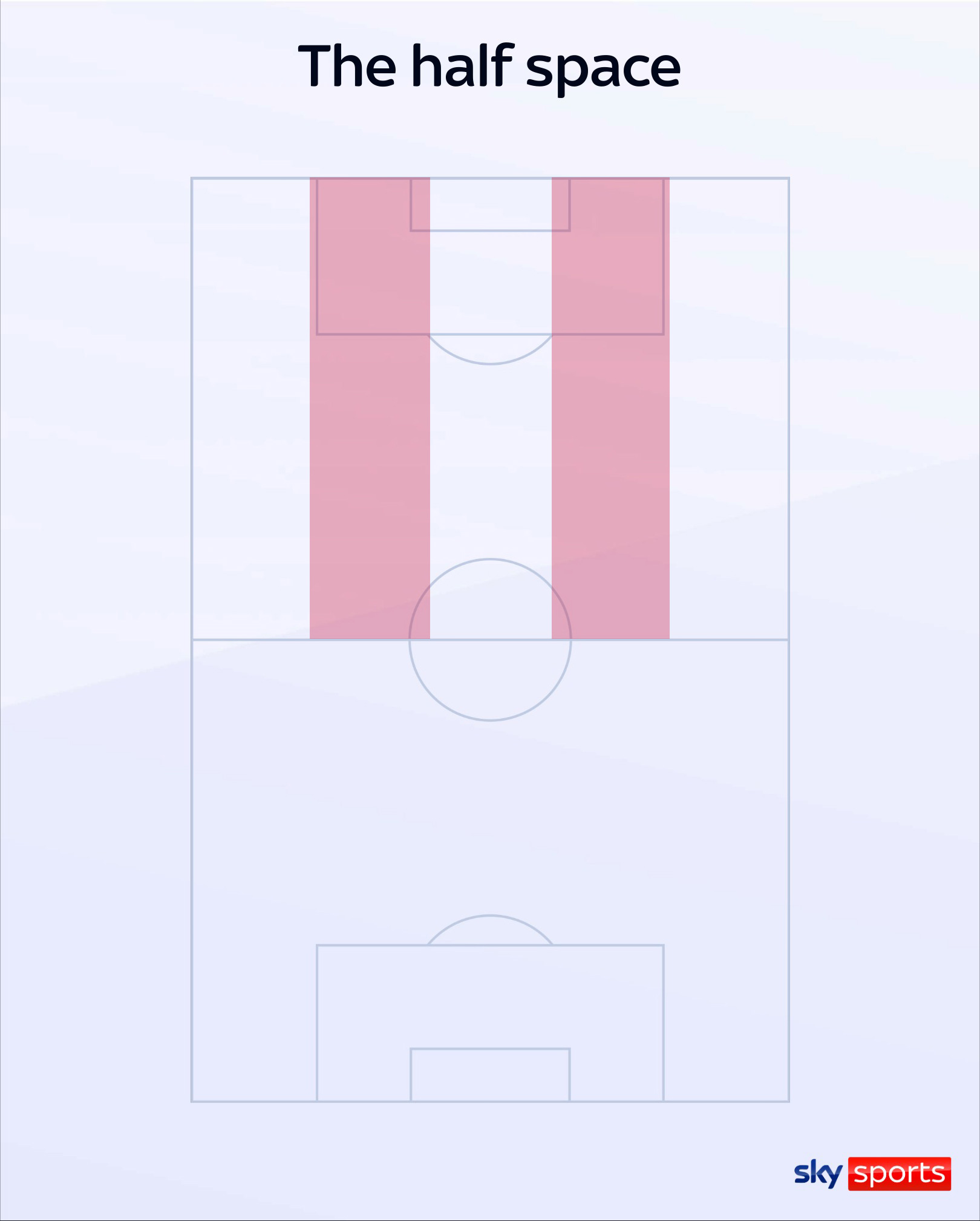

Half space

Think about where the middle of a football pitch is. And then think about the wide areas of a football pitch. The bit in between is known as the ‘half space’.

It is often considered the most dangerous area of a football pitch because that’s where the most creative players do their best work.

Take Manchester City as an example. If Erling Haaland is occupying the two centre-backs in the centre of the pitch, with Savio and Jack Grealish causing havoc in the wide areas, then Kevin De Bruyne and Phil Foden are occupying in the half spaces in between.

It is a relatively quieter area of the pitch which attacking midfielders target to find space. And if you give them that space, they will punish you.

Half turn

Another one you hear quite a lot. “The way Player X takes the ball on the half turn…” What is that all about?

Imagine you’re passing the ball forwards to a player. If that player has his back to you, then he has fully turned. If he has his back to goal, then he’s not turned at all.

The half turn is the middle, when the player receives the ball side-on, allowing him to receive the ball then act on it in one movement to gain that extra space in attack.

Channel

A striker that can run the channel, as well as knit together play as well as find the back of the net is pretty much complete in the modern game. But what is the channel and why is it important for forwards?

The channel typically refers to the space between opposition players. Channels divide areas of the pitch both horizontally and vertically.

An example of a vertical channel that forwards may look to exploit could be between a full-back and the centre-back. Horizontally a channel could be the space between the midfield and the defence.

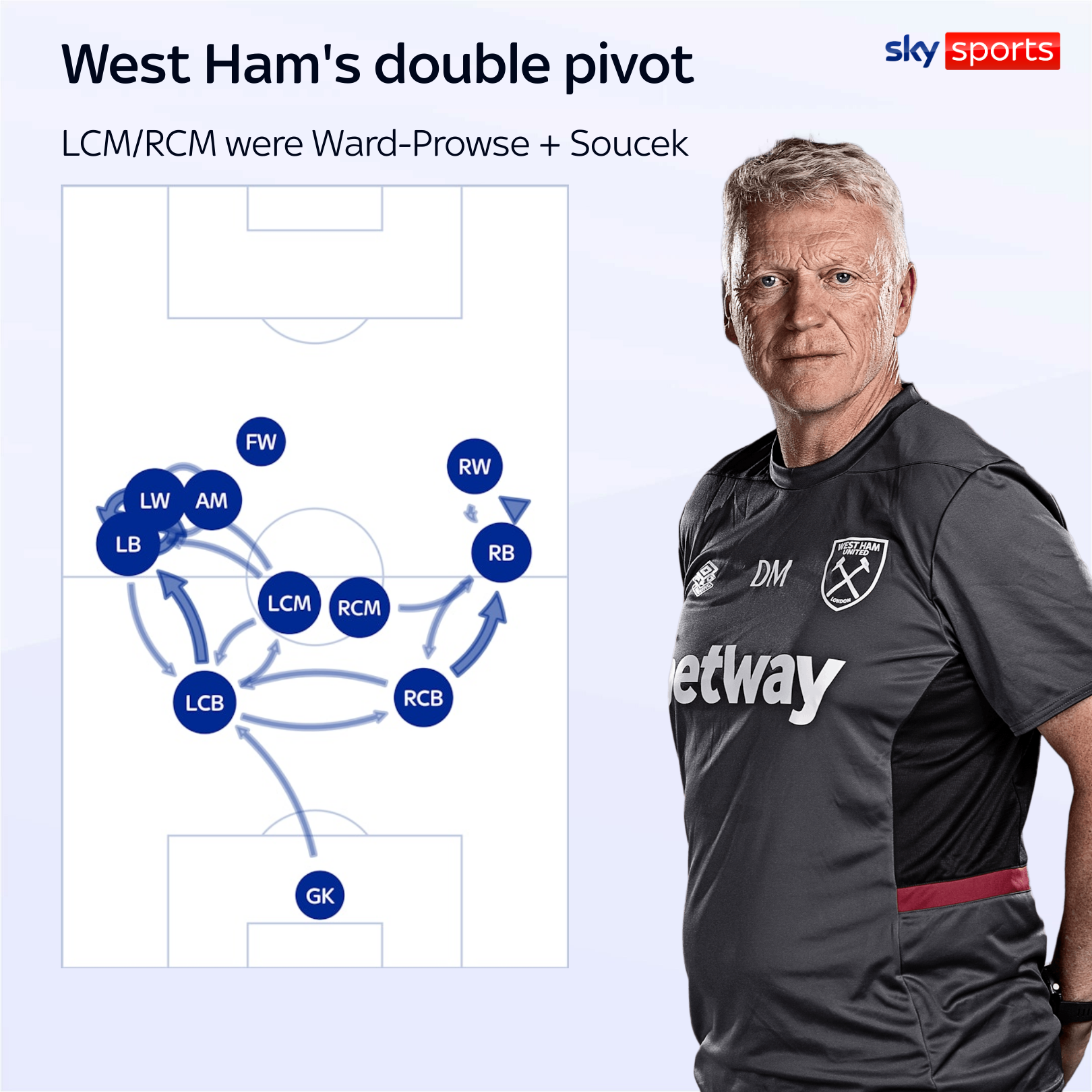

Double pivot

From Jose Mourinho’s title-winning Chelsea sides to Mauricio Pochettino’s Tottenham and Ole Gunnar Solskjaer’s Manchester United, the double pivot has anchored some of the most notable teams across Premier League history.

A pivot refers to the holding midfielder in a formation. When it is ‘doubled’, it refers to two midfielders anchoring a midfield.

A successful example of a double pivot is Nemanja Matic alongside Cesc Fabregas in Chelsea’s 2014/15 league-winning side under Mourinho. Matic would sit deep, often dropping in between the likes of John Terry and Gary Cahill at centre-back while Fabregas fulfilled a role that allowed him to be slightly more advanced, using his eye for a pass to support the attacking midfielder.

West Ham also had a solid double pivot last season with James Ward-Prowse and Tomas Soucek. When one went forward, the other would stay defensive.

And when there is only one defensive midfielder – Declan Rice holding while Cole Palmer, Phil Foden, Jude Bellingham all play ahead of him for England against Greece as an example – that’s known as a single pivot.

And as a general rule of thumb, players who play as a defensive midfielder are known as a No 6. If a midfield three has two attacking midfielders then those two roles are known as No 8s. And if a midfield three has just one attacking midfielder, then that is a No 10.

Man-to-man marking

In open play it’s a dying art but the notable Ander Herrera job on Eden Hazard in 2018 shows man marking can still have a part to play in a tactical approach. Man-to-man marking is all about what it says on the tin, individual players staying tight opposition players when out of possession.

Marcelo Bielsa’s Leeds United side were notorious for this out-of-fashion risqué approach where his players each had a man to cover and keep track of.

In set-piece scenarios, where man-to-man marking is a little more common, you’ll often see defenders stay within touching distance of opposition attackers, in attempt to prevent an effort on goal.

Zonal marking

While man-to-an marking is all about keeping tight with individual players, with zonal marking the emphasis is placed much more on marking space or ‘zones’ on the pitch. This is much more of a common approach you’ll see managers take in open play as well as from set-pieces.

The method is less contingent on opposition shape and allows teams to defend as a unit, decreasing the risk of players being isolated.

Marking zonally means that defenders should rarely free up space given that this approach allows greater strength in numbers within a team structure.