Since the end of World War II the U.S. has been the unrivaled global health leader through both Republican and Democratic administrations. U.S. public health agencies have set the scientific gold standard for biomedical research, medical product approvals and public health. They fund international research, support resilient health systems and work side by side with scientific agencies on pandemic preparedness.

All this, and far more, is at considerable risk in a second Trump administration, with vast implications for health worldwide, particularly for the most vulnerable.

Let’s start with funding, where President-elect Donald Trump promises to slash global health assistance. Elon Musk, incoming co-head of the advisory “Department of Government Efficiency,” has already expressed support for eliminating all foreign aid. And Project 2025, widely seen as the right-wing blueprint for a second Trump administration, subjects humanitarian assistance to withering criticism, calling for “deep cuts.” In 2020 Trump’s final budget proposed cutting global health programs by 34 percent, including for maternal and child health, nutrition, family planning and infectious diseases. While bipartisan support for global health prevented deep financial cuts then, Congress today is far more aligned with Trump’s “America First” agenda, including its hostility to foreign aid.

On supporting science journalism

If you’re enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

That’s bad news because the U.S. is the world’s largest funder of global health, providing four times more bilateral international health assistance than Germany, the government providing the next most. . In 2022 the U.S. provided more than $12 billion in funding to global health initiatives to support low-and middle-income countries through its huge network of bilateral and multilateral funding, as well as on-the-ground technical assistance and training.

As a result, the U.S. is a leading funder of core global health initiatives, including the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria—since the organization’s launch, the U.S. has provided 36 percent of its total funding—and Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance, which increases equitable access to lifesaving vaccines (about 24 percent of contributions from 2021 to 2025).

The National Institutes of Health has a $48-billion budget, which it invests in biomedical and behavioral health research that benefits the world. The agency’s remarkable record of success includes developing lifesaving antiretroviral therapies for HIV/AIDS and mRNA technologies such as COVID vaccines. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention took a leading role in the eradication of smallpox and the ongoing global polio eradication campaign. The NIH’s Fogarty International Center has trained almost 8,500 scientists from low- and middle-income countries since 1989.

President George W. Bush signing of HR 5501, the Tom Lantos and Henry J. Hyde United States Global Leadership Against HIV/AIDS, Tuberculosis, and Malaria Reauthorization Act of 2008.

WENN Rights Ltd/Alamy Stock Photo

Started in 2003 under then president George W. Bush, the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) is due for reauthorization in March 2025. PEPFAR has invested $120 billion in the global HIV/AIDS response. That’s by far the largest commitment made by any nation to address a single disease in history, saving more than 25 million lives. Congress may cut PEPFAR funding or make funding contingent on refraining from crucial work supporting sexual and reproductive health and fighting discrimination, all key to stopping HIV/AIDS.

At the height of the COVID pandemic, Trump made what one of us (Gostin) called a cataclysmic decision: delivering a letter to the United Nations secretary-general indicating an intention to withdraw from the World Health Organization. While President Joe Biden reversed the decision, Trump now has four years to withdraw, as recommended by Project 2025.

Yet Trump has another choice: make a deal. He should keep the U.S. a member, contingent on the WHO undertaking vital governance reforms such as increased transparency and accountability.

He will almost certainly drastically cut U.S. financial support for the WHO to a level equal to, or below, China’s contributions. If Trump chooses to withdraw or slash funding, the effects could be devastating. The U.S. is the WHO’s largest member-state funder, representing 22 percent of all WHO-assessed dues. Without U.S. funding, or with “greater restrictions on federal dollars to WHO,” as Project 2025 outlines, the organization’s programming would be hollowed out, and its pandemic responses capacities would be diminished, endangering health everywhere. And given financial and political pressures in Europe, governments there may not compensate for the loss of U.S. contributions.

If countries believe, as we do, that WHO is indispensable, they must stand up and fight for the agency. We cannot imagine a world without an empowered WHO, with its constitutional mandate on the right to health for all.

The WHO was born in 1948 with powers to negotiate health treaties, such as the Framework Convention on Tobacco Control. On June 1, 2024, the World Health Assembly adopted a major revision to its International Health Regulations (IHR), which ensure early detection and reporting of disease outbreaks and scientific exchange. Not only did the U.S. drive IHR negotiations, but the nation’s Health and Human Services secretary Xavier Becerra threatened to walk if its final amendments were not adopted—and they were. That shows the determination and influence of the U.S when it actively engages.

Those 2024 amendments won’t take effect until September 19, 2025. Because of his distrust of international agreements, President-elect Trump could issue major reservations to the IHR or withdraw entirely. Either way, U.S. national security is at stake because the IHR fortify pandemic preparedness and response. The U.S. must remain a party for the good of the nation and the world.

The 2024 World Health Assembly granted the Intergovernmental Negotiation Body (INB) one further year to negotiate a new Pandemic Agreement. With Geneva negotiations at a stalemate, the question becomes whether Trump will block any U.S. participation, given that he had previously asserted that the Pandemic Agreement would benefit other countries at the expense of the U.S. Many Trump allies have stoked disinformation that the Pandemic Agreement would cede U.S. sovereignty, a claim that has been widely debunked.

Inevitably, a second Trump term will threaten reproductive rights globally. He is almost certain to again cut funding to the U.N. Population Fund (UNFPA), the U.N. agency that works to ensure universal access to sexual and reproductive health services. This time the agency stands to lose more than $160 million, more than double the amount cut during Trump’s first term.

Further, Trump is likely to reinstate or expand the global gag rule, which withholds health assistance to organizations that provide any abortion-related services, even if they use non-U.S. funds. In his first term, with devastating effect, Trump expanded the domestic gag rule to include all U.S. global health assistance, not only family planning assistance, as the rule was applied during previous Republican administrations. A second Trump administration might not only quickly reinstate the global gag rule but further broaden it to cover all U.S. foreign assistance.

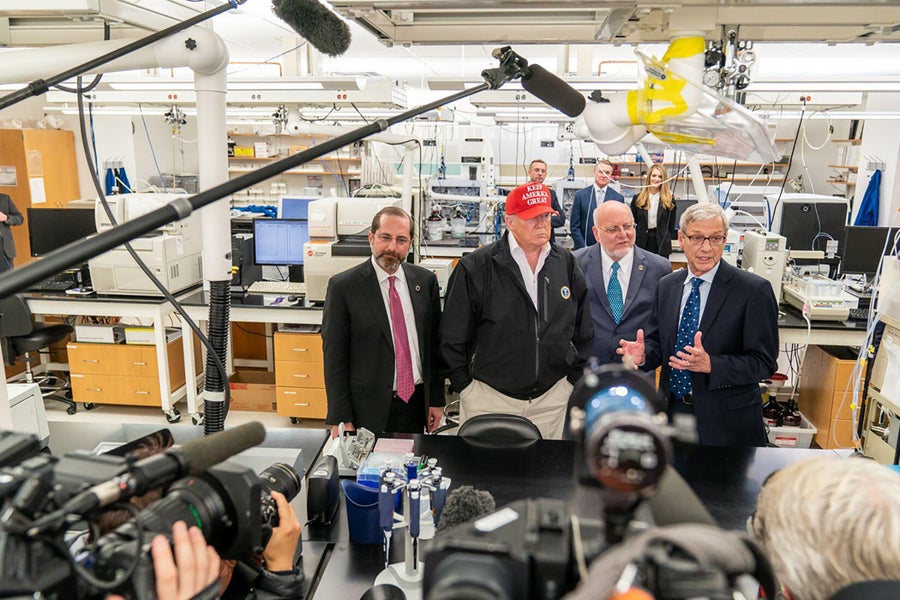

President Donald Trump speaks with reporters during a visit to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in Atlanta on March 6, 2020.

PBH Images/Alamy Stock Photo

Finally, the CDC is bracing for cuts, given the politics surrounding its role during the pandemic. For more than three quarters of a century, that agency has worked to protect and improve health security. With a network of offices in more than 65 countries, it has a vital role in funding and logistical support, field training and emergency rapid response. Along with reduced funding, there is danger that the CDC’s political leadership will fail to act consistently with the recommendations of the agency’s own scientists.

Since the creation of WHO, the world has embraced international cooperation in health. Throughout those decades, the U.S. was the unrivaled global health leader, recognizing that we all inhabit a single planet and face common health threats. In other words, on matters of health and the environment, we are all in this together. That ideal of international cooperation and solidarity will be sorely tested in the next four years.

This is an opinion and analysis article, and the views expressed by the author or authors are not necessarily those of Scientific American.