[ad_1]

Steve Jobs, Bill Gates, Elon Musk, Jeff Bezos—men dominate the tech industry. In 2021 men made up 75 percent of employed computer scientists and 84 percent of employed engineers in the U.S.

And that’s cause for concern. Consider the misuse of generative artificial intelligence tools for videos: deepfake pornography overwhelmingly targets women and—alarmingly—some teenage girls. Would you trust an all-male team of software engineers to make responsible and informed decisions about such tools? Though software engineers are a tiny sliver of the world’s population, the products they make can have enormous impact on the rest of society.

Compared with men, women generally express more ethical and privacy-related concerns about AI and place a higher priority on safety and accountability. The tech industry needs more diverse perspectives to guard against the very real harms that AI technologies can bring into our world.

On supporting science journalism

If you’re enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

My latest research as a psychologist and educational researcher unveils a major roadblock to achieving a more representative workforce, however: tech stereotypes that emerge remarkably early in children’s development. In research published this month, my colleagues and I found that by age six, kids already see girls as worse than boys at computer science and engineering.

We also discovered that gender stereotypes are not the same for all STEM subjects (science, technology, engineering and math). In fact, math stereotypes are far less gendered than many researchers have often assumed. This nuance helps point to new ways to broaden participation in STEM fields. Most prior research to date has focused on stereotypes that girls are “bad at math.” But my colleagues at the American Institutes for Research and Cambridge University and I noticed mixed evidence as to whether children really hold that belief. Some studies do indeed show that kids have absorbed the stereotype that girls are worse than boys at math, but other studies find the exact opposite.

We set out on a five-year-long expedition to synthesize more than four decades of past research on children’s gender stereotypes about abilities in STEM. We compiled a massive dataset of more than 145,000 children across 33 nations whose stereotypes had been measured in various ways. For instance, a study might ask kids, “Are girls or boys better at computer coding?”

A clear pattern emerged: tech stereotypes are far more male-biased than math stereotypes. In other words, kids are more likely to see computer and engineering ability as “for boys” than they are to do the same for math ability.

And this divergence across STEM fields begins early. For example, 52 percent of six-year-olds think boys are better at engineering, whereas 10 percent think girls are better—an early male bias of 42 percentage points. Computing also shows male bias at age six, though to a lesser extent. But for math, the fraction of six-year-olds who say boys are better (28 percent) is about the same as those who say girls are better (32 percent), showing no clear winner among young kids. (The remainder of kids did not see one group as better than the other.) These differences mirror related patterns among adults. For example, 40 percent of employed mathematicians but only 16 percent of employed engineers in the U.S. are women. Still, it’s surprising that kids as young as age six can have such nuanced beliefs about different STEM fields. Do six-year-olds even know what “engineers” are?

In a broader context, the findings for math are less surprising. Girls earn better math grades than boys, for instance. Further, studies find that kids view success in school as being “for girls,” generally. These contextual features could reduce male bias in math, especially when it is perceived as a school subject.

Kids’ tech stereotypes, meanwhile, likely come from cues outside the classroom, such as depictions of male computer nerds in films, news media and TV shows. Of course, young kids may also misperceive what computer scientists and engineers do. For instance, many English-speaking children assume that engineers fix car engines because “engineer” contains the word “engine.” Kids could then transfer masculine stereotypes about auto mechanics to engineers.

At early ages, girls are somewhat insulated from these masculine stereotypes. That’s because of a phenomenon that developmental psychologists call in-group bias. Ever heard girls chant “Girls rule, boys drool”? Children aged five to seven tend to strongly favor their own gender. Math is one example: in general, boys favor boys and girls favor girls in early childhood when asked about who does well in that subject.

This in-group bias even protects the youngest girls against tech stereotypes, to an extent. For instance, among six-year-old girls, 34 percent say girls are better at computing, whereas only 20 percent say boys are—exhibiting a female bias.

But this pattern rapidly changes with age, as cultural stereotypes replace in-group bias. At ages eight to 10, the number of girls who say boys are better at computing starts to outnumber those who say the reverse. This male bias further increases in middle school and high school. These sharp shifts could limit girls’ future aspirations for high-demand tech fields, such as AI.

In contrast, boys of all ages consistently favor boys in all STEM areas, on average. Despite this relatively stable bias in STEM, boys rapidly learn stereotypes that can hold them back when reading and writing. By their senior year of high school, a clear majority of boys (72 percent) think girls have better verbal abilities, and only a small minority (10 percent) think boys have better verbal abilities.

Our findings collectively indicate the need for targeted action. Initiatives for “girls in math” or “girls in STEM” may fall short of addressing the most entrenched stereotypes. Instead these efforts need a strategic focus on the most male-biased fields, such as tech.

The tech gender gap isn’t set in stone. In 1984 women were 37 percent of computer science college graduates—the highest fraction compared to any other point in time. Yet today this figure hovers around 20 percent. Cultural changes, such as marketing computers to boys, may have driven girls and women out of the field. If the change was cultural, why can’t we dial back the clock on that particular aspect?

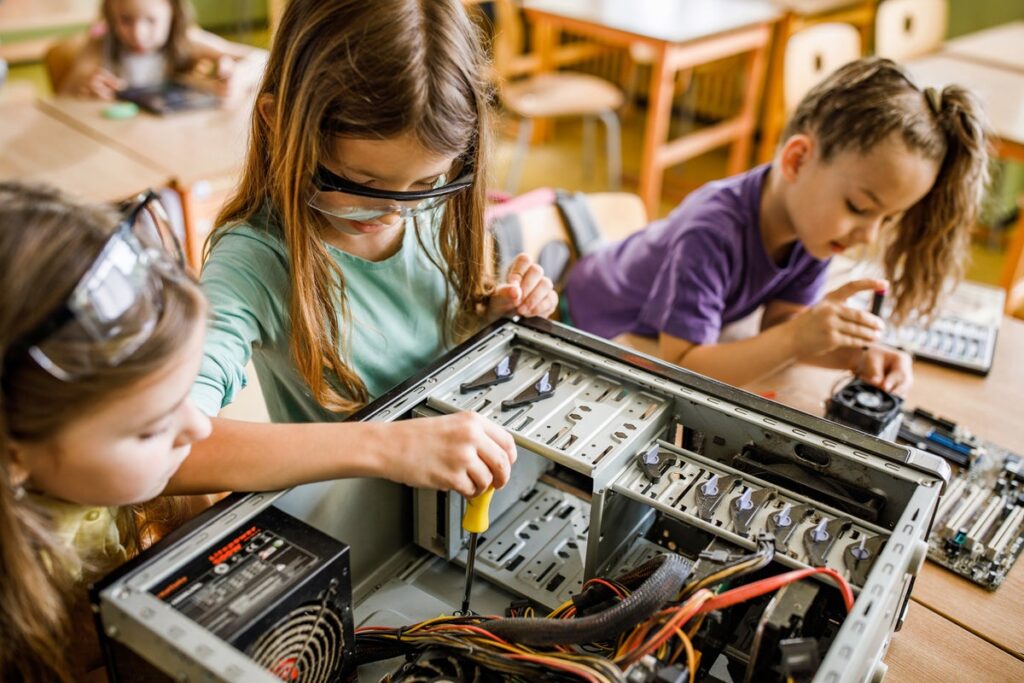

To address tech stereotypes, we need a national commitment to expand quality engagement with these fields in early childhood and elementary education. Research shows that early positive experiences with programming and robotics can ignite girls’ curiosity and interests before stereotypes set in and drive girls away. Free apps such as ScratchJr allow children aged five to seven to learn coding basics by programing interactive stories and games, for instance. But a lot more research is needed to be sure what early approaches will actually narrow gender gaps.

With early positive exposure, girls might lean less strongly on stereotypes to guide their future decisions, such as when choosing high school course electives. That is, early engagement in tech sets a foundation for success in later grades and career stages. These steps to broaden participation in STEM will benefit both tech and society. Consider Rebecca Portnoff, head of data science at the nonprofit Thorn, who uses her computer science expertise to develop AI tools and safety-by-design guidelines that aim to stop the creation and spread of child sexual abuse images. AI technologies have tremendous potential to transform society. Having diverse voices in tech will help harness that power for social good.

Are you a scientist who specializes in neuroscience, cognitive science or psychology? And have you read a recent peer-reviewed paper that you would like to write about for Mind Matters? Please send suggestions to Scientific American’s Mind Matters editor Daisy Yuhas at dyuhas@sciam.com.

This is an opinion and analysis article, and the views expressed by the author or authors are not necessarily those of Scientific American.

[ad_2]

Source link